For most of us, insurance is not a very sexy subject to begin with; it makes many people cringe! I don’t know many people who enjoy contacting their insurer – except when something goes wrong – or dealing with their insurance contracts. But we still have a more or less close relationship with the insurance sector because we take out contracts (civil liability, housing, vehicle…) whether it is out of obligation, in anticipation of a risk, or for a whole host of other good or bad reasons.

The agricultural sector also has its share of insurance contracts. For example, there are the classic contracts that you can have as a private individual, but also a whole range of more specific insurance policies such as those for agricultural machinery, buildings, seeds, or crop losses. In this blog post, we will focus exclusively on crop insurance, also known more broadly as climate insurance, for two main reasons. The first is that, in case you haven’t heard, a major climate disruption is underway. And the human race is responsible for it as the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) says – without any further ado – in its 2021 AR6 report. This climate deregulation is already starting to hit the agricultural sector in the face. The second reason is that agricultural weather insurance in France is about to be reformed. At least, this is what we should understand from the report by Frédéric Descrozailles, a member of parliament, which was submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture in the summer of 2021, and some of whose amendments were voted on at the beginning of 2022, with a view to implementation in early 2023.

I would like to stress that some elements of this dossier are focused on France – in particular everything that revolves around the reform of agricultural insurance that is taking place there at the moment. Nevertheless, I hope that readers outside our beautiful country will find the background, insights and discussions in this blog post of interest.

As usual, for the readers of the blog, this article is based on video interviews with actors of the sector (whose names you will find at the end of the article) whom I thank for the time they were able to give me. Several articles, reports and seminars have allowed me to complete the feedback from the interviews.

Enjoy reading!

Figure 1. Frost control in Burgundy vineyards in April 2021. The buds had come out very early in 2021 following a particularly mild winter. The April 2021 frost completely reshuffled the cards and put French winegrowers in a catastrophic situation.

Soutenez Agriculture et numérique – Blog Aspexit sur TipeeeClimate change and the cost of damage

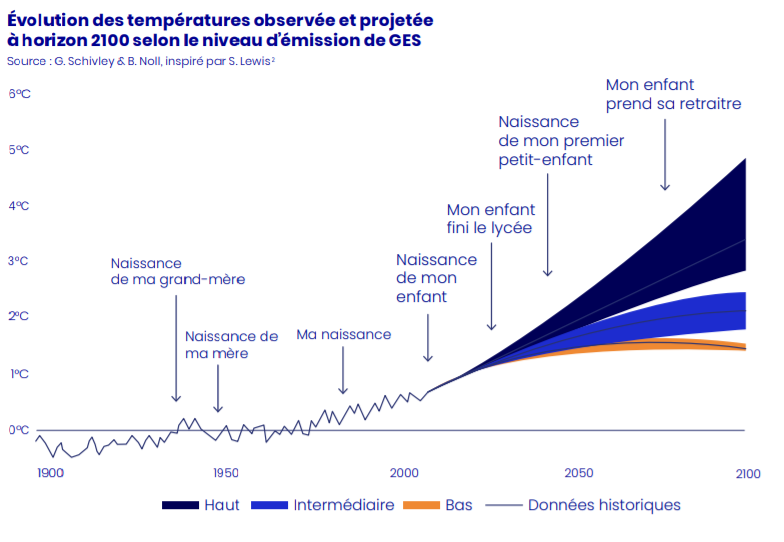

The publication of the first part of the IPCC’s sixth report has once again sounded the alarm. There is no doubt that human activities are causing widespread and rapid global warming (Figure 2). The extent of the warming we will experience will obviously depend on our cumulative CO2 emission scenarios, but experts already agree that the widely publicised threshold of +1.5°C of warming by 2100 compared to the pre-industrial era will almost certainly be exceeded.

Figure 2. Observed and projected temperature changes by 2100 under three GHG emission scenarios. Source: Territorial Resilience Strategy Reports, Shift Project, 2021. Volume 1 – Understanding.

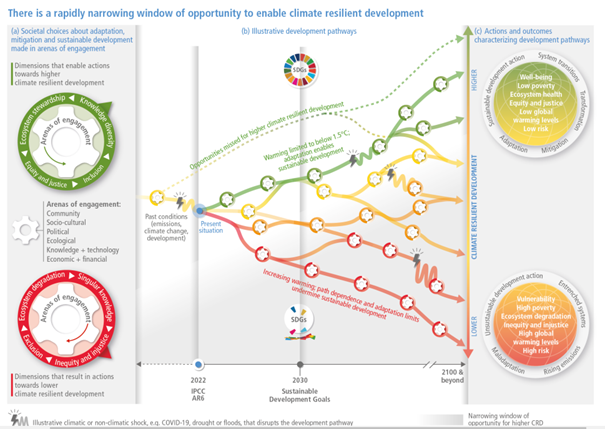

The second part of the IPCC’s sixth report, published at the beginning of 2022, insists on the fact that we have only a very short window of opportunity – of the order of a few years – to act before we enter climate trajectories from which it will no longer be possible to escape (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Illustrative climate or non-climate shock, e.g. COVID-19, drought or floods, that disrupts the development pathway. If we do not act quickly, we can see that the orange and red trajectories never return to the green and/or yellow trajectories. Source: IPCC, 2022.

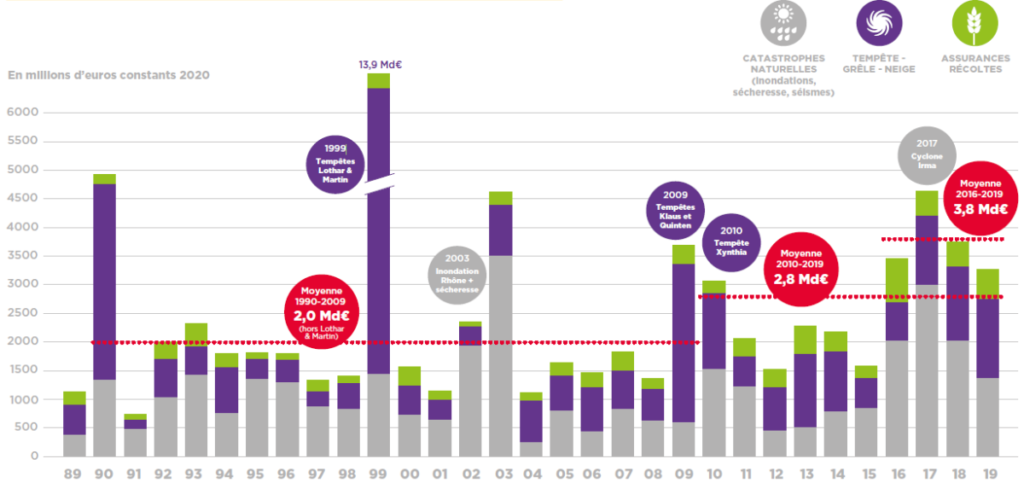

The damage of ongoing climate deregulation is already widely visible, and it is starting to hurt the wallet. In its 2021 annual report, the insurance broker Aon estimates the damage generated by natural disasters at around 343 billion dollars in 2021 worldwide, after 2017 (519 billion dollars) and 2005 (351 billion dollars) [Aon, 2021]. France Assureurs – the federation of insurers and reinsurers operating in France – has recently highlighted the trend of increasing claims costs paid by insurers since the 1990s (Figure 4). The figure also shows the strong evolution of indemnities for agricultural weather insurance – the “crop” insurance that we will discuss at length later in this blog.

Figure 4: History of claims paid by insurers following natural hazards in France. Source: France Assureurs, 2021

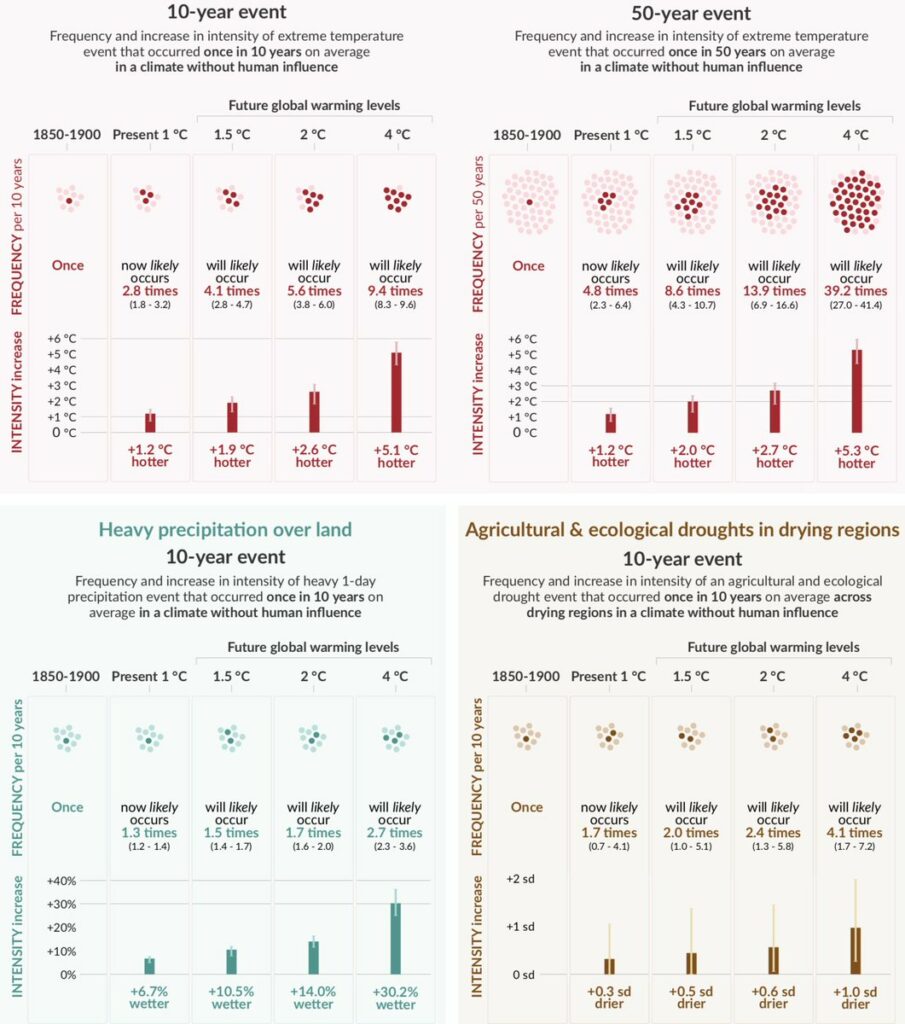

And these trends are not about to stop… The latest IPCC AR6 report of 2021 is very clear on the probability of occurrence and the intensity of the climatic events that could be faced with a few extra degrees on a global scale (Figure 5). It shows, for example, that with only 2°C more warming in 2100 than in the pre-industrial era, an extreme temperature event will occur 5.6 times more often in 2100 than in the period 1850-1900, with this event being on average 2.6°C warmer. We wish our dear farmers around the world well. And to continue on the agricultural sector, the same report predicts that under the same 2°C warming scenario, an agricultural and ecological drought event will occur 2.4 times more often in 2100 than in the 1850-1900 period.

Figure 5: Projected changes in the intensity and frequency of extreme temperatures over land, extreme precipitation over land, and agricultural and ecological droughts in dry regions. Source: IPCC, 2021

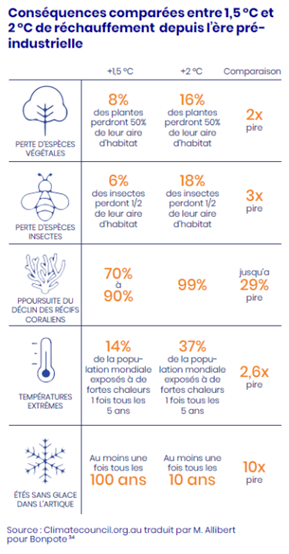

And I would like to take this opportunity to add a few keys to the consequences of such warming for the biosphere, in order to break out of our rather too human-centric prism of thought (Figure 6). Whether in terms of the loss of plant species, the loss of insect species (which is widely highlighted in the latest IPBES [Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services] report), or the continued decline of coral reefs, we can see that the dynamics are extremely variable and non-linear with a warming planet’s temperature.

Figure 6. Comparative consequences of 1.5° and 2° of global warming since pre-industrial times. Source: Climatecouncil.org.au, 2021

All this is of course if we limit warming in 2100 to +2°C compared to pre-industrial times. We are not heading in that direction at all… In the “business as usual” scenario we are following, i.e. without any change in our lifestyle, we are at least heading towards +4°C warming scenarios.

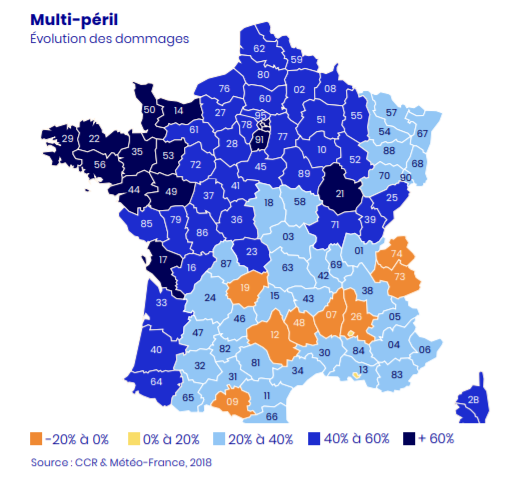

Did you think that insurance companies had paid out a lot of money in recent years? But you haven’t seen anything yet, folks! In association with Météo France, the Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR) has produced a map of the evolution of natural disaster damages between 2018 and 2050 (Figure 7). In their 2021 report, France Assureurs (still the same as above), estimate that the cost of natural hazards will continue to grow at the rate of a doubling every 30 years [France Assureurs, 2021]. By 2050, we could expect to have to take twice as much money out of our pockets as we have had to take out in the current years.

Figure 7. Spatial distribution of the evolution of damage from natural disasters between 2018 and 2050. Source: Territorial Resilience Strategy, Shift Project, 2021. Reproduced from JRC and Météo France report (2018).

While the cost of action to limit or adapt to climate disruption may seem high at the moment, it is out of all proportion to the cost of inaction that we may face in the coming years (and are already seeing). In 2006, former World Bank chief economist and vice president Nicholas Stern published his eponymous report in which he argued that the cost of inaction far outweighed the cost of prevention. The Stern Review estimated the cost of inaction, depending on the scenario, to be between 5% and 20% of global GDP, compared to 1% for action. Similarly, if insurance seems expensive to you, non-insurance is just as expensive. As an example, French farmers affected by the exceptional floods of 2016 had to borrow almost 5 billion euros from their bank to get through the bad year. Farmers’ debt capacities were largely saturated by these short-term, non-productive loans, which could have been used for example to finance transitions or simply to invest. And society also bears the losses indirectly through the loss of productivity and competitiveness of the agri-food sectors.

When we talk about agricultural insurance, we should not consider that the risks linked to extreme weather events only affect farmers. It is by considering the entire agricultural sector – input suppliers (seeds, fertilisers, machinery, etc.), cooperatives, farmers, traders and processors – that it becomes clear that all players can be affected if agricultural production is affected by a climatic event. A problem for the farmer and it is the domino effect… Because an uninsured farmer is also a supplier or a client who is not solvent for a cooperative or an input supplier.

Global trade in agricultural products allows financially well-off consumers to be satisfied because a local production deficit due to a climatic event can be compensated for by an import from a non-affected country, regardless of the transport costs. The agricultural risk is then hidden from consumers as long as the climate risk does not become systemic at the global level. The current crisis in Ukraine is a reminder of this. Yield risk due to climatic hazards, on the other hand, permanently affects the individual income of all farmers, anywhere in the world.

Some common insurance knowledge bases

Hazards, risks and vulnerabilities

Many of us take out insurance policies (civil liability, housing, vehicle, etc.) but do we really know what insurance is? Insurance is a transfer of risk. Behind this rather simplistic phrase there are actually many concepts that need to be borne in mind.

The first, and certainly the most important, is that behind insurance there is a risk. If there is no risk, there is no insurance. The insured, who bears a risk (a climatic risk for a farmer, for example), transfers his risk to the insurer by taking out an insurance contract. The insured wants to get rid of his risk, so he sells it. Paradoxically enough, we hear people say that an insurer “buys” a risk, whereas we agree that the insurance contract is paid for by the insured. In reality, it should be understood that the transaction between the insurer and the insured finances the service of transferring the risk from one actor (the insured) to another (the insurer). In France, the insurance supervisory authority (ACPR – Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution) is very careful to ensure that insurance contracts do indeed involve risk transfers, and not something else, a way of making sure that people do not transfer money of any kind without risk (from one subsidiary to another, for example)

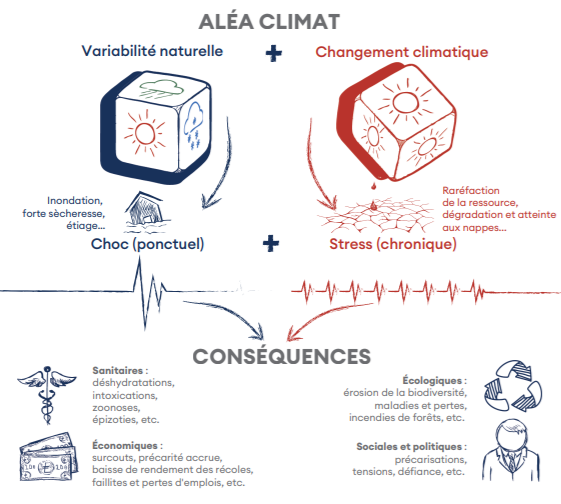

Let’s quickly take the opportunity to make a small aside of vocabulary and clarify the differences between a hazard, a risk, and a vulnerability. A hazard is a phenomenon (natural or technological) that is more or less likely to occur in a given area (Figure 8). A risk, on the other hand, is the possibility of a hazard occurring and affecting a population that is vulnerable to that hazard; vulnerability can be of any kind to infrastructure, health, etc. In other words, if there is no vulnerability, there is no risk. A storm in the middle of the ocean is not a risk for the population. It is a strong climatic hazard, certainly, but since no population is vulnerable to this hazard, we will not consider it a risk. This notion of risk is nevertheless rather subjective because not everyone sees vulnerability in the same way. In the remainder of this document, we will use the terms hazards and risks in a similar manner to make it easier to read, but keep in mind that the concepts are nevertheless different.

Figure 8. Climate hazard – the conjunction of natural variability and climate change. Source: High Council for the Climate, 2021

Insurers and re-insurers

Anyone can insure themselves: individuals, companies, states (for example, states can insure themselves against natural disasters to mutualise the risk of drought, or to protect their budgets to compensate farmers against a future climatic hazard). But perhaps most surprisingly for those unfamiliar with the sector, insurers also insure themselves. They use reinsurers (e.g. Swiss Re, Munich Re, Partner Re; “Re” should be understood as “Reinsurance”) to whom they transfer their risks. One of the reasons for the existence of reinsurers is to cushion natural disasters that affect an entire portfolio of policyholders. The reinsurer pools its risks through a portfolio of policyholders that is as diversified as possible. But isn’t that what insurers already do? Yes, but not on the same scale. When a large area is affected (in the case of a hail storm, for example), it is the entire country that is affected and the losses are enormous at the national level. An insurer whose portfolio of policyholders only included policyholders in this territory would be ruined because it would have to pay an insurance premium to all its policyholders at the same time. This is too big a risk for the insurer to manage alone, so it will tend to reinsure itself. The primary insurers carry the risk. The reinsurers are the second net, they are there in case of a hard blow. In the context of weather insurance, reinsurers diversify risks by insuring several different geographical areas, hoping that there will be compensation between the areas (considering that there is little chance of a storm occurring at the same time in Chile, France and Indonesia). Reinsurers will thus tend to be more international players. Note, however, that some reinsurers may also be insurers on the side for certain classes of business. Note also that insurers may split insurance contracts into several parts (known as proportional insurance) and share them with another insurer or a pool of insurers, in which case it is known as co-insurance (the same thing may happen with reinsurers, in which case it is known as co-reinsurance).

Insurers and reinsurers are not philanthropists. Their job is not to make money for the insured. Insurers are there so that the cost of claims is lower than the insurance premiums (if the insurer makes money, the insured loses money). And the insured, when he or she takes out insurance, is not supposed to consider that he or she will make money. The use of an insurance product is not a means of generating income: it would not make much sense to calculate an “ROI” (return on investment) of an insurance contract for an insured because it is normally supposed to be negative. Over the length of his insurance contract, the policyholder loses money but, in exchange, the policyholder limits the volatility of his income statement. The policyholder buys peace of mind in exchange for a kind of annuity paid to his insurer (unless the insurer decides to lose money on his insurance contract…). It is important to understand that insurance contracts allow to limit the jolts that everyone could have on their profit and loss account (or bank account for individuals). For example, if my house burns down, it is a risk of ruin for me because I cannot assume this risk alone. In the same way, if I kill someone while driving my car, the amounts to be paid will be so huge that I cannot afford not to insure myself. Insuring your car is compulsory for this reason, and it can be said that if this insurance was not compulsory, few people would use their car for fear of having an accident that they could not pay for. On the other hand, if my mobile phone is stolen on the bus, I can consider that this is not a risk of ruin and I can imagine not insuring myself for this type of risk. To draw a parallel with agriculture, if, as a farmer, I can bear the financial ups and downs of several successive bad productions, I might as well keep the risk to myself and not take out an insurance policy. Agricultural weather insurance protects against hard times that cannot be absorbed by the farmer’s savings alone. It is therefore possible to self-insure in order to keep the benefits of the insurance and not to depend on possible variations in insurance rates in the contracts taken out with my insurer.

It is important to understand that insurers and reinsurers will insure random risks. From the moment the risk becomes certain, it is entirely predictable and thus becomes uninsurable. There is therefore a very important distinction between what is in the realm of randomness (and which can be insured) and what is in the realm of tendency (which cannot be insured). Insurance cannot indeed insure a trend (e.g. a global warming trend), but within a given trend, insurance can insure a hazard. Another way of putting it is to distinguish, in the case of climatic hazards, between what comes under the heading of risk volatility, which is typically part of the insurance logic, and what comes under the heading of the level of guarantee allowing for compensation for a loss of production.

Like the banking sector, the insurance sector is also highly regulated. Insurers have equity (i.e. capital available to settle high-cost claims) – as do reinsurers – and are supervised by supervisory authorities (the ACPR in France, for example). There is a professional guarantee fund, but the state is not supposed to intervene. The regulator requires insurers and reinsurers to assess their solvency on an ongoing basis (solvency ratios, risk measures, risk scenarios and impacts on solvency, etc.). The European “Solvency 2” regulation makes it clear that the insurer is obliged to cover claims up to 99.5% within one year (in other words, this also means that the insurer is not supposed to be able to pay claims once every 200 years). The insurer must therefore have sufficient equity to cover the claims. As an insured, we need to make sure that our insurer (or re-insurer) will be able to afford to pay in the event of a claim because if the insurer goes bankrupt, the insured will have to pay the cost of their claim, and the domino effect starts to kick in quite quickly. In the markets, insurance companies are rated. When taking out an insurance contract, policyholders must therefore take an interest in the rating of their insurer. Not all insurers have a rating (in practice, only insurers that are listed on the stock exchange and/or issue bonds on the financial markets have ratings). Every policyholder is entitled to ask about the credit rating of an insurer as defined by the regulations, but you have to know something about it….

How are insurance rates set then? Insurers need to develop risk models (e.g. climate models, earthquake models, etc.) to calculate the risk of a claim falling on them. Insurers anticipate the frequency and cost of each claim in order to price their insurance contract and thus evaluate the insurance premium they will ask to pay. The most difficult thing for insurers to do is to assess the uncertainty associated with climate risks, particularly because these uncertainties vary over time. Insurers constantly assess the so-called loss ratio, i.e. the ratio between the insurance premiums paid by the insured and the claims paid by the insurer. If the ratio is higher than 1, the insurer loses money because it pays out more money than it recovers through its contracts. This is expressed as the ratio between outgoings (management fees, commissions paid, claims provisions and claims reimbursement) and receipts (premiums and contributions received). To give an order of magnitude, the management costs of the insurance contract for the insurer, i.e. excluding the estimated cost of claims, represent about 20% of the total insurance contract price. These include the cost of reinsurance, the cost of tied-up capital, the cost of underwriting contracts (marketing costs), the cost of administering contracts, or even the time spent on managing the expertise and the cost of travelling to the field.

Pricing is not easy either because we do not always know exactly what has happened in the past and what will happen in the future. An example is asbestos. When asbestos was considered to be carcinogenic, plaintiffs started to ask for compensation. Between the moment the problem is understood and the trial takes place, many years can pass. The insurer then finds himself pricing in a rather obscure environment where he does not always have a good idea of the risk involved.

Insurance works in cycles and contracts are re-priced every year. Re-pricing every year is not a legal requirement. However, as insurers’ solvency models are 1 year in regulation, insurance contracts tend to be too. In theory, insurers could very well be able to run their risk models over 5 or 10 years. And insurers would be well advised to do so over a number of years in order to mutualise risks, both in space and in time. However, in the case of subsidised insurance contracts (we will see the case of agricultural insurance below), the insurer is dependent on eligibility for the subsidy and this eligibility is fixed by decree every year. If the State decided to modify the specifications for obtaining the subsidy, the insurer would no longer be able to provide the insured with the subsidy. Even if some insurance contracts are offered over many years, there would in fact always be a clause to redefine the rates annually if there were problems. Let’s get back to the point. If there are several years in a row of low claims, prices will fall. If, on the other hand, the number of claims increases, the prices of insurance contracts also increase. When the insurance premiums paid by policyholders are not sufficient in relation to the claims experience of the insurers, the insurers increase their prices and regain their health over time. At the time of the World Trade Center attack, insurance on the airline fleet increased enormously. The few insurers who had the courage to continue offering insurance policies made a lot of money because there were very few claims afterwards.

Insurers and reinsurers use in-house teams and external consultants (data scientists, climatologists, etc.) who offer modelling services and require skills and expertise in fluid mechanics, weather forecasting and data analysis. Agrometeorology is important here to find damage modelling formulas adapted to the crops that are covered. But not all risks are so easily modelled, specific risks are the most complicated to consider. Modelling the exposure of a territory to a risk remains a difficult task.

Insurance in the face of climate deregulation in agriculture

In France, in the agricultural sector, total insurance premiums can be roughly divided into three large blocks of equal size. The first third for building and animal insurance. The second third for agricultural machinery. And the third for weather insurance. With the climate deregulation we are experiencing, the situation will change tomorrow because crops will be the assets most exposed to climatic events. The risks to which French agriculture is exposed are actually going to get worse. There is a trend towards a form of tropicalisation of the climate, which is combined with a historic halt to the increase or stability of production potential. In France, the recent consultations of the “Water Conferences” and the “Varennes de l’eau” have shown that the subject is completely topical.

It is clear that insurers have a short-term vision, except perhaps for civil liability. If previously, it was the impact of a company’s direct activity that was compensated, we are starting to see indirect activities come to the fore. For example, recently the Port of Los Angeles had to compensate residents living near the port for the CO2 and fine particles emitted by the trucks feeding the port. With the ongoing awareness of climate change, any negative impacts that certain types of activity will amplify will be subject to litigation.

We have seen above that weather events are increasingly hurting the wallet (Figure 3). These events are becoming more frequent and more expensive, not least because as we build more and more infrastructure we are undeniably increasing our vulnerability. Insurers do not have enough equity to manage major weather disasters and therefore insure themselves “in excess” with reinsurers (as an insurer, I consider, for example, that beyond a loss of 2 million euros, I can no longer deal with the settlement of claims alone). Re-insurers are stronger with a more diversified portfolio of policyholders, have more equity and capital, and can therefore take this risk in excess.

Nevertheless, insurers and reinsurers are beginning to ask more and more questions. In the area of risk forecasting, they are realising that climate models built with past data to predict what might happen in the future are no longer relevant. There is no longer any stationarity in the climate. Models must become deterministic, including physical, economic and sociological parameters and not just statistical parameters to understand the risk. Crossing issues and hazards requires the development of much more complex models, to anticipate and better predict, and price risks. One of the people I interviewed made the following joke: “the statistics we use to price risks are a lantern to light up the future and we carry it behind our backs”. The fact is that the past no longer explains the future in terms of hazards, which may also explain why a good part of the results are chronically loss-making, with the possibility that reinsurers and insurers are losing interest in certain types of risks.

With climate change, regulations are also changing. Insurers are starting to be rated (ESG ratings – Environment, Social and Governance). The carbon impact of insurers’ assets (particularly the type of bonds purchased) must be published. In short, we can dream that with climate change, certain types of polluting activities will no longer be insured (even if we agree that this is not really the trend we are seeing at the moment…).

Insurance, one of the many aspects of risk management in agriculture

Agriculture is one of the sectors that emits the most greenhouse gases, but also the most sensitive to the consequences of climate change. It is therefore absolutely necessary for the agricultural sector to reduce its footprint but also, and above all, to be able to adapt to the risks incurred. And these risks are numerous: frost, heavy rain, flooding, excess humidity, storms, heavy or excessive snow, hail, excess temperature, drought, or lack of radiation. One could even imagine many others, not directly climatic, such as: no germination, absence of fruit set…

This dossier is devoted to insurance in agriculture, and more particularly to climatic insurance (we will come back to all this very quickly). However, it is important to understand that agricultural insurance is part of an overall risk management strategy and that there are many levers that can be used to adapt to the current climate change. These levers – in many forms – can be used independently or in combination:

- Agronomic levers: Choice of varieties adapted to the local environment and resistant to climate change, varietal mix, sowing density, direct sowing under cover, staggering sowing dates, preserving the value of grassland, crop diversification, changing the breed of animal, bringing forward the sowing period, reducing the number of livestock

- Technical levers: Installation of irrigation and/or drainage systems, anti-hail nets, photovoltaic panels, etc.

- Economic levers: Increase in self-financing capacity, setting up of precautionary savings (DEP) during difficult years, subscription to one or more insurance contracts,

- Strategic levers: diversification of activities on the farm, reorientation of marketing channels, reorientation towards labelled production systems, autonomisation of one’s farming system, carrying out processing activities on the farm to increase the added value produced, reduction of energy dependence on the farm, anticipation and analysis of risks on the farm through training

One of the first actions, perhaps the most important one, consists in acting in prevention of climatic hazards thanks to different agricultural techniques which allow to be less dependent on climatic conditions.

Agricultural insurance

Indemnity insurance

There are two types of “weather” or “crop” insurance in agriculture:

- So-called “indemnity” insurance is insurance that compensates farmers on the basis of an assessment of the damage carried out by an expert on the farm. We will come back to hail insurance and multi-risk climate insurance (MRC)

- So-called “parametric” or “index” insurance, which compensates farmers on the basis of the deviation of an “index” or “parameter” from the expected

Note that the term “crop insurance” does not mean the same thing to everyone. I will use it here in a rather broad sense (hail, storm, index insurance, multi-risk…). Some people will only see or think of multi-risk weather insurance, wrongly.

We will review their main characteristics here.

The hail contract

Insurers offer the agricultural sector contracts to insure against the risk of hail. In France, this type of contract represents about half of the climate insurance business. It is an indemnity contract in the sense that the expertise is human and that it is managed in more or less the same way by everyone.

The world of hail insurance has been known for many years by the major insurers in the market. Hail is a ‘named’ peril, i.e. it is a risk that is explicitly listed. Hail insurance operates without subsidy and is a contract that, overall, is balanced for insurers (the loss ratio is around 70 to 80%). This means that the policyholders’ contributions are sufficient to pay the year’s claims and to make provisions for claims where the loss ratio is around 200%, 300% or even more (roughly speaking, when it starts to hail severely…).

Hail insurance contracts are differentiated by hail zone. Insurers have zoniers (maps of hail zones) because the hail corridors are well known. For example, it is clearly known that, in the commune of La Chapelle-en-Vercors, in France, hail falls one year out of two. The apricot trees there are therefore very expensive to insure. Even without a subsidy for this insurance contract, the farmers subscribe because they are aware of the risk incurred and the damage potentially caused to their production. It’s a very real risk, which is frightening, and farmers insure themselves all the more because they know that the state will not intervene in the event of a problem.

The Multi-Risk Climate Contract (MRC)

Multi-risk climate insurance (MRC) was launched in France in 2005 following the droughts and heat waves of 2003, which most of us still remember (report by the Member of Parliament Christian Ménard). Before 2005, the State alone covered this climatic risk thanks to the Agricultural Disaster scheme (this scheme was set up in 1964). This calamity scheme – sometimes called the agricultural calamity fund for short – is financed by the Fonds National de Gestion des Risques en Agriculture (FNGRA); this solidarity fund is fed by taxes paid by farmers and supplemented by the national state budget (this is why there is no VAT in agriculture, as there are already taxes to feed this agricultural calamity scheme). Following the drought of 2003, the budget for the agricultural disasters scheme literally exploded – by a factor of four. The State then organised the deployment of a private insurance industry dedicated to this sector, alongside the State; the MRC insurance was born.

Unlike hail insurance, MRC insurance is subsidised, currently at 65%. Many countries choose to subsidise crop insurance because agriculture is a strategic sector from a government perspective. As discussed above, insurance is one voice among others in the risk management strategy. At the European level, the choice has been made to move from a direct subsidy mode to agriculture (direct CAP aids) to an indirect mode by favouring investment in protective equipment or by subsidising crop insurance. The idea behind the subsidy is to ensure that insurance contracts are spread within farms so that, once they have become commonplace, this subsidy is gradually reduced and the insurance system runs itself.

To return to the MRC, for an MRC insurance contract costing €100, the farmer currently pays only €35 (the contract is 65% subsidised). For a contract set up for the 2022 harvest, the farmer pays his insurance premium in October 2022 and the subsidy is paid around March 2023. In the decision to subsidise an insurance contract, it was decided by the government that a subsidisable contract was one that addressed not just one risk but several (the MRC contract must contain 17 weather hazards to be eligible for subsidy). The idea behind this is that there is no point in subsidising a contract that only takes into account one hazard if the final objective is to secure the farms. Hail is included in MRC insurance but some insurers have a subsidised basic policy and an additional hail policy (a specific hail policy as discussed in the previous section) with a specific deductible for each plot independently (the basic MRC policy covers hail with a deductible per appellation or crop, which is not necessarily advantageous…) We will come back to the concept of deductibles a little later.

The MRC insurance thus enables farmers to benefit from risk coverage that covers all climatic risks and is tailored to their individual needs. Until 2022, there were a number of requirements for subscribing to the MRC insurance policy. In particular, a winegrower had to have all of his land covered, and for field crops at least 70%. In addition to the primary objective of securing farms, the MRC contract had several associated interests. For the farmer, it is already a gain in visibility and management, in the sense that it is simpler to insure his entire farm at once than a small part here and a small part there. For the insurer, this contract is a way of diversifying his customer portfolio; he sells more insurance than if he only sold hail insurance. For the administration, but also for the insurer, it is also a dimension of simplicity that must be seen. The DDTs (departmental directorate for the territories, french acronym) will be responsible for collecting and verifying that the contracts are eligible, for checking the unit prices of the contracts, for verifying that the areas correspond to the declared CAP areas, and for verifying that all of the vineyard areas of a farm are covered if it takes out an MRC insurance contract.

At the same time as crop insurance was launched, legislative support did not intervene much to develop the agricultural disaster fund and to allow disaster and insurance to coexist. The crop insurance system was initially conceived as a new system added to the agricultural disasters system, with the two systems coexisting and articulating each other as best they could, with practices varying by department. Initially, the State’s intention was to let private insurance develop until insurance was sufficiently widespread, and then to remove the crops concerned by the insurance from the agricultural disaster scheme. The idea was that, in the long run, only private insurance would remain in place and the agricultural disaster scheme would gradually disappear from the scene. Thus, in 2009, field crops were removed from the agricultural disaster scheme. Viticulture followed in 2011. The scope of the agricultural disaster scheme was thus reduced, as the wine-growing and field crop sectors were deemed to suffer from insurable risks. The positioning of the calamity scheme or, more rigorously, the scope of intervention of the part of the FNGRA that compensates agricultural calamities, is centred on what is deemed uninsurable. Other crops (meadows, arboriculture, market gardening) remained eligible.

Since 2005, about 30% of field crops and vineyards are insured on the crop contract. For other crops, the figure is less than 5%. The situation has not changed since 2011. The level of insurance is far from being the same everywhere on the planet. Worldwide, the United States, China and India account for three quarters of agricultural insurance premiums paid by the agricultural sector (CICA, 2020). Although the population of these countries is still very large, it is clear that the entire world’s agricultural population is not insured in the same way. In a 2020 report, the International Confederation of Agricultural Credit stated that the value of agricultural insurance premiums in 2016 was around 7% of the value of agricultural production (CICA, 2020). Worldwide, some of my interviewees gave me the figure of 20% of crops insured, and barely 2% of grassland production.

Currently, to have access to insurance, farms must have a grazing number (and therefore have already made a CAP declaration) – the application for insurance is made during the declaration of the CAP file.

Why aren’t more farmers insured with MRC?

It will be difficult to fully explain why only 30% of wine and arable farmers are currently insured with an MRC policy (and even fewer in fruit, vegetable and grassland farming). The explanations are extremely broad and multi-dimensional. A first explanation is perhaps rather psychological. A sort of denial in which the farmer convinces himself that the risk will never happen to him or his crops. In the Beauce region, in France, some farmers felt they were out of the loop until the catastrophic floods of 2016. It is true that the culture of risk among farmers is not extremely well developed, and the training offered is almost non-existent (we will talk about this in the last part of this blog post). But it is also true that farmers are also gamblers in many ways. This is also understandable in the sense that they evolve in a particularly unstable and risky environment.

There is already a first risk linked to the production itself or to the yield on the farm, each crop being subject in its own way to a very large number of events that influence the level of production. When contracting the sale of their production, farmers are also subject to harvest quality criteria. The risks to prices are particularly numerous. For example, there is so-called “imported” instability, linked to the global financial markets and the variability of raw material prices, “natural” instability with climatic and natural hazards that impact production in terms of yield and quality, and “endogenous” instability, which pushes farmers to anticipate the selling price of a product and which produces fluctuations that are uncorrelated with the market. For example, the explosion of the selling price of a cereal will push many farmers to cultivate this cereal the following year, which will generate an overproduction and consequently a sharp drop in the prices of the following year’s crops. Another source of uncertainty is production costs, i.e. all the operational and structural costs required to cover a full production season. We can even add to this the risks on a slightly wider scale, with operational risks, linked to the farmer himself (death, illness, disability) or to his farm (fire, theft, damage, etc.), financial risks since the farmer may be subject to variations in rates on his various contracts or to problems with the liquidity of his farm account, or institutional risks linked to changes in policies, regulations and standards (e.g. a new regulation on an input, a change in the price of a product, a change in the price of a product, etc.): A new regulation on an input, a regulation on the import or export of certain commodities. .)

Farmers are also not necessarily very used to taking out insurance policies for their crops and will therefore prefer to self-insure. Farmers are more used to insuring their buildings and equipment.

Another reason given is that farmers believe that the state will always be there to intervene if there is a real problem. We saw above that field crops and vines were removed from the agricultural disaster scheme in 2009 and 2011 respectively. However, following the spring frost in 2021, we saw the state intervene by putting money back on the table. In 2011, the agricultural disaster funds were also triggered in anticipation of a drought that did not occur. By intervening ex-post, the State sends the message that it will always be there, and farmers no longer necessarily see the point of protecting themselves with a private insurance policy.

There may well be a misunderstanding of the system, with an offer that often appears complex, with subsidy rules that are difficult to understand and a system that is far from obvious. Some contracts require a very early subscription period in relation to the agricultural season (e.g. a subscription at the end of December for a season that starts in March/April), which requires farmers to position themselves in advance and to anticipate risks. Although this blog post is absolutely clear (you have to know how to throw yourself a few flowers), understanding the insurance mechanisms in place was not an easy task… The current reform seeks to harmonise and simplify the processes in place for multi-risk climate insurance, but you still have to roll up your sleeves and spend some time to really understand what is going on.

Some farmers will also tend to complain that the insurance premiums offered are too high, and that the policies are poorly priced for their risk. The concept of the ‘Olympic benchmark’, which is the average level of yield that is insurable on the farm, is often brought up. With several bad years in a row, the Olympic benchmark decreases and with it the level of insurable yield, and the insurance contract becomes much less attractive to the farmer.

Even if this type of contract is subsidised, farmers consider the price too high and do not want to insure themselves. Once again, there is the idea that you are only happy to pay if you are sure that it will do you some good. Can you really blame them? Is the argument about the cost of insurance contracts really justified? We will also come back to this later.

Let’s also add that in some fields, the current offers are not numerous or considered relevant enough to be interested in.

Anti-selection and moral hazard: the main phenomena of indemnity insurance

Four phenomena or types of risk associated with indemnity insurance can be distinguished.

The idiosyncratic or ‘specific‘ risk is a component specific to each farmer. It is an independent risk that does not affect all people at risk at the same time. It is a sort of specific marker of a farmer. For example, every farmer has a risk of having one of his farm buildings burn down. It can be agreed that this risk is independent of the risk that his neighbour has of his building burning down. The idiosyncratic risk is independent between each insured and is therefore a mutualisable risk.

Systematic or systemic risk is risk that does not affect a particular individual but a group of farmers with a common characteristic, such as geographical area or type of crop. Examples of systemic risks are floods, droughts and diseases (when widespread). The disadvantage of this risk is that it is non-diversifiable and therefore cannot be covered by conventional insurance mechanisms. The commonly used method of hedging is to add a risk margin to the contract price of the insurance, which varies according to the probability of the risk occurring.

Indemnity insurance is subject to problems of information asymmetry, in the sense that the insurer and the insured do not have the same level of information about the riskiness of agricultural production and production practices. Indeed, farmers are expected to be better informed about both simply because they are in the field and manage their farms. This asymmetry of information generates two problems well known to insurers: anti-selection and moral hazard.

Anti-selection or adverse selection is the fact that farmers who take out insurance are those who are exposed to above-average risks. When signing an insurance contract, the insurer does not know the exact risk of the insured, and will therefore be tempted to increase the price of the insurance contract in order to cover itself against the individuals presenting the greatest risk. The insurer then finds himself in a situation where only farmers with bad risks – basically, risks that hurt and are likely to happen – insure themselves because only for them is the cost of the insurance premium justified. A farmer who knows that his land is subject to relatively little risk will not necessarily want to insure himself at too high an insurance premium. An insurer’s portfolio of insureds will therefore tend not to be representative of an average risk in an area. The insurer has more bad risks than good risks in its portfolio. It must be said that within a territory, whatever its size, some areas are subject to greater risks than others, some plots of land are more frosty than others simply because the topography is very different.

Moral hazard, on the other hand, is the phenomenon that leads farmers to adopt riskier production practices when they are insured. Two types of moral hazard can be distinguished: ex-ante (prior) and ex-post (after the fact). Ex-ante risk occurs when the farmer voluntarily modifies his practices – for example by reducing his consumption of inputs – in order to reduce or modify the distribution of yields on his plots and thus receive compensation via his insurance contract. This is referred to as ex-ante risk for the insurer because no loss has occurred on the plots. The ex-post risk concerns the risk of fraud, i.e. a farmer may neglect a damaged plot in order to recover or increase compensation.

To limit the problems of asymmetric information, one way out for insurers is to set up deductibles and have experts visit the field. Although the insurer is often seen as a thief in the sense that the insured has an increasing tendency to wait to win back his initial stake (the idea that because one pays for insurance, one should necessarily get something back), it must be noted that if there were no expert appraisal in the field, the insurer would surely pay much more than he should.

Margin and turnover insurance

The main current crop indemnity insurance formats focus on yield or production risk, i.e. a loss of production quantity. We are entering a field that is more of a banking than an insurance nature.

In terms of coverage, certain “turnover” insurance policies are beginning to develop, the objective not being to cover a price risk directly but to integrate a price dimension into the coverage. Price risk is not covered directly by insurers because it cannot be pooled, even on a global scale. At the climatic level, when a drought occurs in one place and not in another, the events are independent (to a certain extent for the most fussy readers). In terms of price risk, if Nebraska and the Corn Belt have a problem with maize, the global price will rise – the events are no longer independent. The current solution, which is not widely used, is to insure the yield via MRC insurance and to insure the price via futures markets. The possibility for the farmer to hedge already exists. But insurers and reinsurers will not really insure a price risk directly. In the United States, for example, turnover insurance does not meet with unanimous approval. Some dispute its principle on the grounds that it would lead to public expenditure even when crop prices are high. It would be better, in their view, to restrict state aid to the provision of a safety net against climatic hazards, limited to covering the main production costs. Others, on the contrary, denounce the fact that premium subsidies and compensation paid are proportional to production and thus favour large farms and the concentration of agricultural land for the benefit of a few. As a result, they are calling for a reduction in the support paid by the programme to the largest producers.

Some insurers are also working on “margin” insurance, which changes the situation in terms of logic, especially for extensive systems. Let’s take the example of two cereal farmers with tight situations and a risk of poor yield. Let’s imagine that these farmers are wondering whether or not they should apply a final nitrogen application to their plots. Taking the last step to try to get your yield (in this case, applying a last nitrogen application) can be considered as a risky operation for agriculture. There could therefore be many cases where the person who does not take the last step comes out ahead if he or she has the insurance net (we have talked about ex-post hazards, we are in that case here). If, on the contrary, an insurer had secured the production of this cereal farmer with a margin insurance, perhaps this nitrogen contribution would have been carried out. Everyone wins, so it changes the logic of the insurance system.

Agricultural insurance reform in France

How MRC contracts have worked since their creation ?

In France, until 2022, the multi-risk climate risk management contract is based on three main pillars:

- A first, unsubsidised level, which in fact corresponds to a sort of deductible that the farmer will have to pay anyway if he has a claim (this is the farmer’s remaining liability). This deductible is the way in which the insurer or insurance broker can change the cost of the insurance premium paid by the farmer (by increasing the deductible, the insured reduces the insurance premium and vice versa). Some insurers also offer deductible buy-back, which is an additional guarantee where the farmer pays more for the insurance premium but in exchange pays little or no deductible in case of an accident.

- The second level corresponds directly to private insurance. It is this second level that is subsidised. In France, it was decided to subsidise climate insurance premiums with a share of the European CAP (Common Agricultural Policy) budget, and more particularly that of the second pillar: the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). In the example presented above of a €100 MRC insurance contract subsidised at 65%, the farmer would in fact only pay €35 while the CAP would be used to pay the remaining €65. The farmer thus bears a limited part of the cost of the insurance contract he takes out.

- The third level corresponds to public intervention by the state with the agricultural disaster scheme. This third level should not be considered as a subsidy but as an aid, in the form of a principle of national solidarity.

Too easy, super clear, I understood everything! Three different levels with a deductible, private insurance and public intervention by the state. Yeah, not so fast… Let’s add a little complexity with the levels of coverage and the different types of contracts that can be faced. If you have followed everything, you will have understood that part of the cost of an insurance contract is directly linked to private insurance with part of the cost of the insurance covered by the CAP (this is the second level we have talked about). I gave the example of a 65% subsidy to get an idea of the underlying mechanisms. This 65% actually corresponds to a first level of guarantee (base level) and is linked to a whole bunch of criteria (national references and a scale to set a ceiling on the insured capital, the proportion of the farm’s surface area to be insured, compensation for quantity losses, the triggering threshold [corresponds to the level of crop loss from which the subsidy takes place – for example, there must be at least 30% yield loss], and a minimum deductible) which we are not going to go into so as not to get too lost.

It should therefore be understood here that France mobilises the second pillar of the CAP (EAFRD) to finance up to 65% of the amount of the insurance contribution corresponding to the first level of guarantee (base level). This first level of guarantee aims to give the farmer the means to restart a production cycle. France has also gone further in subsidising this private insurance contract by adding the possibility of subscribing to optional supplementary cover, subsidised at a lower rate than the basic level (45% here compared to 65% for the basic level), allowing the farmer to reduce the excess and adapt the cover to his own risks. A third level of cover, known as optional, also exists to allow the farmer to further adapt the contract taken out to his characteristics. This third level is not subsidised by the EAFRD. Note that crop insurance contracts benefiting from these subsidies cannot receive any other aid financed by State, local authority or European Union credits

Let us also add a point on the fact that two main types of crop insurance contracts are subsidizable:

- the so-called “crop group” contracts, the principle of which is to pay specific compensation for each type of crop as soon as the production loss observed following a disaster for this crop is higher than the triggering threshold. It is not a contract per plot but per batch of plots on which the same crop is grown. Note that for this type of contract, a minimum area per type of crop must be insured. For example, in order to have an MRC Arable contract on a farm, at least 70% of the farm’s arable area must be covered by the contract

- the so-called “on-farm” contracts, the principle of which is to pay compensation if the total losses on the types of crops insured following a disaster are higher than the trigger threshold. The main difference with the so-called “crop group” contract is that here there is a mutualisation between the types of crops insured, as gains on one type of crop can compensate for losses on another. To subscribe to this contract, there are, as for the previous contract, coverage obligations. It is required that at least 80% of the area of the farm’s sold crops be insured and that at least two different types of crops be insured.

Why reform?

The main advocates of the current reform point out that the current system of compensation for losses due to climatic hazards is out of date. Several reasons are given:

The historical players in agricultural insurance are losing money. From 2016 onwards, the system of the main insurers has gone into a tailspin (we spoke above about the major floods that took place). Claims escalated to premium loss levels of almost 200% (insurers paid out twice as much as they had received in insurance premiums). Until 2021, the ratios did not fall below 100%. Years like 2016 are no longer exceptional and the consequences of climate change continue to develop (events in frequency and intensity). For the major insurers, the system has become unsustainable. Insurers have had to review their tariff conditions and cover under pressure from their reinsurers and the supervisory authority (ACPR).

The MRC multi-risk weather policy has a penetration rate of only 30% among farmers. There are not enough farms that subscribe to the policy to be able to balance the insurers’ risk portfolio. This is the anti-selection phenomenon we have been talking about, which means that the good risks will leave the portfolio, leaving only the bad risks in the majority. In traditional insurance, rates are smoothed by zone (municipality, department, etc.). If smoothing is only done with bad risks, a farm with a low risk will have a very unbalanced rate compared to one with a much higher risk. However, some will argue that the fact that there is ‘only’ 30% take-up of crop insurance contracts at present for field crops and vines is not necessarily a sign of malfunctioning. It may also be the fact that some farms prefer to self-insure and manage the risk on their own because they are strong enough.

The rather awkward cohabitation between private insurance and public intervention by the State via the Agricultural Disaster regime is said to be the cause of an excessive eviction effect on farmers in the sense that they rely too much on State support in the event of a hard blow (we have spoken, for example, of State intervention for the 2021 frost on vines when viticulture was no longer covered by the Agricultural Disaster regime) The link between the DDTs (departmental directorate for the territories, french acronym), which are in charge of managing the agricultural disaster scheme on the ground, and private insurance is not always very effective, and has sometimes made them more competitive than anything else. The loss rates measured in the two cases are not always the same because local assessments and trigger criteria can be very different (insurers used Olympic yield averages but the agricultural disaster scheme did not take them into account). Farmers can then turn against their insurer or the State, calling one or the other a thief.

The boundary between what is insurable (private insurance) and what is not (public intervention) is absolutely decisive, not least because it is not entirely clear and, moreover, it changes over time (some risks are – or will no longer be – insurable). It should be noted that public intervention by the state in the event of a climatic hazard does not have to take an economic form. Several actions are conceivable (and some have already taken place). Fallow land declared to be of ecological interest can be used in the event of drought. Neonicotinoids have for example also recently been authorised on certain crops. The “Varennes de l’eau” exercise proposed to regulate the supply of methanisers when there were tensions on fodder resources during climatic hazards.

The current complexity lies in the fact that all of these thresholds (deductible threshold, trigger threshold, etc.) and subsidy and aid criteria vary from one crop to another. Up to now, it is indeed by sector that it was decided to change the nature of compensation from the Fonds National de Gestion des Risques en Agriculture (FNGRA) and not by type of risk, even if, strictly speaking, it is a hazard/sector cross-reference that specifies the risks classified as insurable. Some crops, for example, have left the calamities regime because it was considered that the risk associated with these crops was insurable, whereas for others the calamities regime is still available. And yet, as we have discussed, although vines were removed from the scheme in 2011, the state has stepped in for weather hazards in the year 2021

Developments in the reform

The report by Frédéric Descrozailles, Member of Parliament, submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture in the summer of 2021, suggests a number of changes to the current agricultural insurance system. This report already points out three fundamental principles of the upcoming reform.

- First of all, it is a principle of national solidarity, or in other words, the fact that it is agreed that the State will officially reinvest in the current insurance system. I recall here once again that certain crops were taken out of the agricultural disaster regime and were therefore not supposed to be covered by the State in case of strong climatic hazards. By this principle of solidarity, it is considered that agricultural workers cannot finance the insurance schemes they might need by taking part of the wealth they create. However, we could come back to this game of vocabulary in the sense that the agricultural disaster scheme is still financed in part by taxes on farmers. Nevertheless, it is explained that the majority of the budget of this fund will be financed by national solidarity.

- The second founding principle of the report is that of the legitimacy of the State to intervene in agricultural insurance in the sense that it is important to make a clear distinction between what is due to the hazard (and which is insurable by private insurance) and what is due to the trend (not insurable by the private sector and requiring public intervention). The State is therefore present to get involved in the management of exceptional or systemic risks, i.e. those that cannot be insured or that require public reinsurance in the case of phenomena of exceptional scope.

- Finally, the reform is based on the principle of universality, insofar as any farmer wishing to be insured will be able to subscribe to an insurance contract, which was not the case until now.

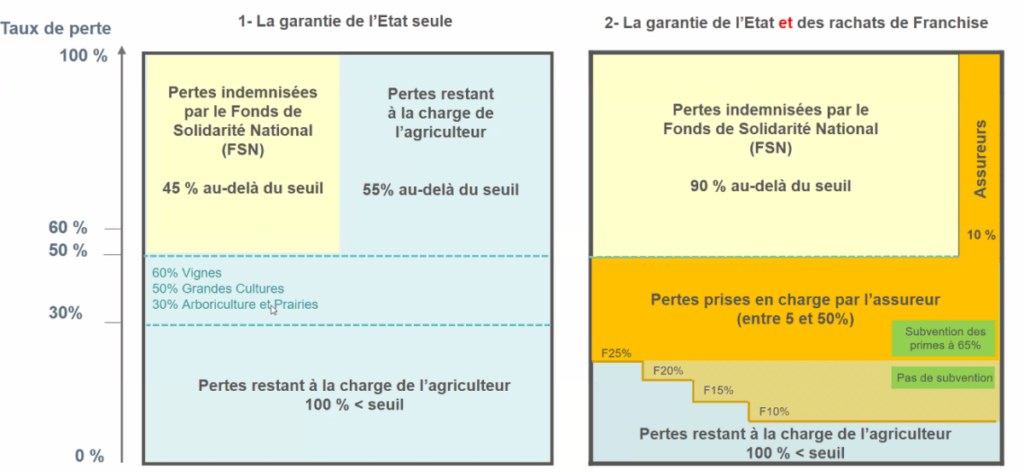

We agree that the proposed reform seeks to harmonise and simplify an initial, relatively complex system, which was not really easy to navigate. Nevertheless, from there to say that the expected result at the end of the reform is biblically simple, I would tend not to get my hopes up… The reform can be summarised in Figure 8!

Figure 8. Crop insurance reform. Source: Pacifica, internal.

Tadaaaa. Got it? The graph on the left is for the farmer who is not insured. The graph on the right is for the farmer who is insured. So far so good:

- For the uninsured (left graph): Below the trigger level (“seuil” in french), i.e. the percentage of crop loss, the farmer receives no aid and has to pay out of pocket. The trigger levels are set at 50% for all crops but it is not impossible that these levels diverge as shown in Figure 8 (60% for vines, 50% for arable crops and 30% for trees and grassland). It should therefore be understood that for a field crop plot where the yield loss is less than 50%, an uninsured farmer will have to pay everything himself. If the crop loss is above the trigger level, the state, via the national solidarity fund, will pay 45% but only for the loss above the trigger level. For example, if a field crop plot suffers a loss of 70%, the state will pay 45% of the amount of the loss, but only for the amount between the 50% and 70% loss. The rest is paid by the farmer. For the uninsured, it is therefore a two-tier contract (farmer and state).

- For the insured (right-hand chart): Below the trigger level, i.e. the percentage of crop loss, the farmer receives no aid and has to pay out of pocket. Unlike the uninsured farmer, the insured farmer has taken out an insurance policy and is therefore compensated for crop losses ranging from 25% (deductible threshold) to 50% loss rate. However, this compensation is not total, the insurer pays between 5 and 50% of the losses – again only for crop losses ranging from 25% to 50% loss rate (these are increments, like what happens to our taxes). I remind you that this insurance contract is subsidised at 65% with a basic level of cover. The farmer, together with his insurer, was able to request deductibles of less than 25% – either by negotiating with his insurer or by having his insurer buy back deductibles by increasing the total price of his insurance contract. If the crop loss is above the trigger level, the state, via the national solidarity fund, will pay 90% (i.e. twice as much as for an uninsured farmer) but only for the loss above the trigger level. The last 10 percent is paid by the insurer. For the insured, it is therefore a three-tier contract (farmer, insurer and state)

In Figure 8, we see here that insurance contracts will depend on the trigger levels. Some advocate identical trigger levels across all crops (at 50%) but it is not impossible that these thresholds diverge as shown in Figure 8 (60% for vines, 50% for arable crops and 30% for trees and grassland). The share of state support (shown as 45% for the uninsured and 90% for the insured) may still vary.

Some thresholds and rates are also likely to change as a result of the application of the agricultural part of the EU Omnibus regulation (there are parts of this regulation for sectors other than agriculture). If fully implemented, this regulation could also allow for changes to the levels of excesses and in particular for the minimum excess to be lowered from 25% to 20%. The Omnibus Regulation also allows for insurance contracts to be subsidised up to 70% (instead of the current 65%). The Omnibus Regulation would therefore reduce the price of the insurance contract for the farmer and also reduce his out-of-pocket expenses in the event of a claim. It must be understood that, by construction, this reform and the potential use of the Omnibus regulation represent a substantial increase in public investment if the penetration rate of crop insurance increases among farmers, since the state would intervene more than before. It was not considered reasonable to take all or even most of this increase from the second pillar of the CAP, even if it were decided to transfer funds from the first to the second pillar of the CAP. Several solutions can be envisaged at present:

- A return to a contribution rate of 11% on agricultural insurance contracts (which had been lowered to 5.5%),

- An increase of two points in the surcharge on car and home insurance contracts that finances the natural disaster scheme (the acronym of this scheme is “Cat Nat” in French),

- An increase in some of the contributions that make up the general tax on polluting activities, in accordance with the principle that activities that have an impact on agriculture (pollution or soil artificialisation, for example, with regard to nitrogen and sulphur oxide emissions or extractive industries) should contribute to financing its adaptation to global warming

It should be noted here that the thresholds of the Omnibus Regulation presented here (20% for the franchise and 70% for the subsidy) cannot be extended, because of WTO trade rules. These are therefore thresholds that cannot be exceeded.

Appraisals between private insurers and the state will be harmonised. The 5-year historical reference of the Olympic average (the average level of yield that is insurable on the farm) will be used for both private and public schemes. Following the reform, the Olympic average combined with the high deductible should exclude the possible over-compensation of farmers.

Two tools will also accompany this reform:

- A pool (or grouping) of insurers that will be set up to mutualise the risks of insurers by crop, but also by territory (provided that the productions are not all sensitive to the same climatic hazards). The pool will mutualise risks and allow actuarial calculations to be made to cover farmers’ risks. With total mutualisation, it is considered that the calculation of insurance premium levels will be as fair as possible. This pooling would allow the insurers, members of the pool, to improve their knowledge of agricultural weather risks, lead to more appropriate pricing and improved loss prevention measures. Insurers could then offer insurance policies that are better adapted to the diverse situations of insured farmers. This pool is also intended to federate all insurers who will distribute crop insurance contracts.

- A committee for the orientation and development of crop insurance (CODAR), a sort of governance body where insurers, reinsurers, farmers and the State will discuss these premiums. The CODAR can be seen as a thermometer that allows us to watch the evolution of the insurance system’s loss ratio. This system is intended to be totally transparent so that all the players can see the level of finance in the insurance system and identify risks that are no longer insurable. This CODAR is therefore a real tool for questioning agricultural trajectories in relation to observed claims. If the loss ratios drift too far, it will be necessary to jointly implement adaptation measures in the territories: cease production, introduce tropical varieties, move production basins, introduce crop diversification, or relocate certain types of production. It will therefore be fundamental to take into account the IPCC scenarios and data, and ideally to study climate disruption scenarios by production basin in order to think about adaptations and adjust a time step consistent with the commercial reactivity of insurers.

Agricultural insurance is not made compulsory, but many incentives are being put in place to encourage farmers to take out insurance:

- The insured and the uninsured will no longer be on the same footing. An insured person will benefit from CAP subsidies for his private insurance contract (second stage of Figure 8) and from state intervention based on the principle of national solidarity (third stage of Figure 8). An uninsured person will not receive any subsidies from the CAP for his insurance contract since he will not have taken out any, and will only receive half the amount of national solidarity that he would have received if he had been insured (the famous 45% and 90% in Figure 8).

- A tax incentive is also in place through the deduction for precautionary savings (DEP). As a reminder, these savings make it possible to deduct a certain amount from one’s income – in particular so as not to pay too much tax in a bad year. These savings are then returned to the farm account in a better year. A farmer who takes out an MRC insurance policy would thus have access to a 100% deduction for precautionary savings up to €50,000 of agricultural profit (compared with €27,000 for a non-insured person), and 30% of profit above €50,000 (compared with 30% of profit above €27,000 for a non-insured person). Be aware, however, that this tax aid may have to be added to the MRC subsidy in order to be included in the total state aid, which is limited by EU regulations.

Insurance & Digital : Index or Parametric Insurance

Principles and functioning of index insurance

Parametric” or “index” insurance is insurance that is triggered, not as a result of the loss itself (as in the case of indemnity contracts), but as a result of the deviation of an index or parameter (weather index, vegetation index, regionalized yield index, disease pressure index, etc.) from the expected. To simplify a little, we could say that indemnity insurance correlates an expert’s estimate of losses with actual losses, whereas parametric insurance correlates the deviation of an index from the expected with actual losses. For example, the insured’s compensation may be triggered by a level of rainfall measured at a weather station near the farm. If this weather station has a sufficiently long data history, both parties, the farmer and the insurer, have identical information on the insured value.

Since parametric insurance contracts are based on the definition of an index, one can be very imaginative – the range of possible solutions is extremely wide. One could insure against a lack of wind for a wind turbine, a lack of radiation for photovoltaic panels, an increase in the price of gas, a lack of water on the Danube. In the agricultural context, one could insure against frost or excess heat (rather with the help of a weather station), drought or excess humidity (rather with the help of satellite data), excess or lack of rain (with a weather station or radar data), hail with hail sensors. We can also think of certain guarantees for actors around the farmer, such as a seed company, with for example guarantees directly integrated into the seeds. The seed company then uses the insurance as a commercial guarantee for the farmer against a failure of the seedling to emerge or a drought. The amount of insurance paid out is often proportional to the percentage change in the actual index value compared to the indicator set in the range of values, or the total amount of the sum insured. If the index used is good in the sense that it correlates well with what is happening on the plot, then parametric insurance works well. If, on the contrary, the relationship is not good, parametric insurance is immediately less interesting… Having an annual review and regular monitoring of the index seems relevant to check that there is no drift.

For the advocates of parametric insurance, this format has many advantages:

- Tensions and awkward moments between the insured and the insurer are already avoided when the insured does not agree with the insurer’s claims assessment results. Claims handling can often be a source of conflict (which is why insurers sometimes use insurance mediators). Here the index is measurable and objective, it depends neither on the insurer nor on the insured. The claim becomes objectifiable. In addition, the adjuster is not necessarily always educational in his report.

- The time taken to process the file is greatly reduced in that the adjuster does not need to go to the field and payment can be triggered directly following the achievement or non-achievement of an index level. The farmer, for his part, can therefore receive his compensation more quickly because he does not have to wait for the end of the campaign and/or the visit of an expert. From a logistical point of view, it is also simpler for the insurer who does not need to develop a network of experts, nor does it need to set up a call centre to receive customer requests for assistance. From an economic point of view, insurers can thus lower their insurance premium rates since the costs of expertise and contract management are reduced. However, this aspect must be put into perspective because it is not this part of the insurance that ultimately costs the most in the total insurance premium (management costs would in fact only represent 10 to 20% of the total cost of the insurance premium). Since it is no longer necessary to make damage assessments, insurers can transfer their risk to reinsurers or to the financial markets by using indices. Even if many producers are affected simultaneously, the insurance company does not go bankrupt because it has covered itself by transferring its risk to a reinsurer.

- Anti-selection and moral hazard phenomena (see the corresponding section) disappear, again because the index is based on objective elements that do not depend on either the insurer or the insured. The risk will be modelled, for example, as purely weather risk. Everything will be defined in the contract and the insurer will not take any risk related to the terrain or the exact type of crops. The insurer will refer to a weather data, a calculation formula and will compensate according to the index.

- Unlike traditional insurance, which calculates an insurance premium according to the frequency of a claim on an average cost, index insurance removes the average cost part and transforms it instead into a fixed cost: compensation of X euros if a threshold is exceeded (one can also have progressive index insurance after triggering). The index and the pricing can be more or less complicated to produce and implement. In viticulture or arboriculture, certain damage thresholds are now relatively well known in the scientific literature or easily estimated to trigger insurance. Index insurance based on heat stress or precipitation can be constructed quite easily on the basis of connected weather stations.

- Parametric insurance also meets the constraints set by indemnity insurance because it is much more flexible. For example, in France, in relation to the minimum area covered, a traditional indemnity policy for hail and storm will require that a vineyard covers all of its vineyard area (100%), whether it wants to insure all of it or not. Some farmers will have capital per hectare to cover for certain plots, whereas an insurer will only want to insure a certain maximum amount per hectare, for example. The procedure can be very simplified with index insurance. For example, an insurer can quote for 20 hectares of cover – with such and such a value covered – without specifying the parcels covered, something that traditional insurance might not cover because of anti-selection. The solutions offered by index insurance are much more tailor-made with deductibles and thresholds that the client can easily refine. Index insurance can insure not only a quantity of product but also the value of a product. It is understandable that a great wine producer, given the selling price of its bottle, would prefer to insure the value of a bottle rather than a quantity of grape juice.

However, one cannot have it both ways:

- Parametric insurance is so different from traditional insurance that simplifying assumptions must also be accepted. There is already an effort to understand and familiarise oneself with the data, and new reflexes to adopt in the sense that a farmer is not obliged to insure 80% of the land on set-aside, nor to consider a past yield over the last five years. The farmer must understand that if the measured data is validated (from a weather station or a satellite), there may not be any compensation despite a loss. However, there is a parallel with traditional insurance in that human expertise is not necessarily perfect either. The index(es) must be understandable to farmers. Simple – even if imperfect – calculation formulas are sometimes more relevant so that the farmer knows how he is covered and can make the link with his agro-meteorological expertise (the risk for index contracts is that they are gas factories because they want to limit a whole bunch of parameters). The issue of the complexity of the index is a reality. For example, let’s imagine a case of freezing temperatures with a 10% loss of yield observed at a temperature of 0°. We can have 0° with 10% humidity, with 90% humidity, or 0° for 1 hour or much more. With parametric, farms accept the notion of reducing risk at a well-priced price. The risk is reduced but not cancelled. It is not the same comfort as with traditional insurance where, in this case, the farmer can protect between 10% and 90% of the crop loss, and it is the actual crop loss that will be compensated. There is therefore a risk that the farmer will interpret index insurance as an ambiguous lottery.

- The farmer will potentially have to equip himself and invest in equipment (for a parametric insurance on frost, for example, a weather station is needed). To continue with the weather stations, if we wanted to be very precise, we would need a huge mesh on the ground. Between the top and the bottom of a valley, even without many kilometres separating them, you would need several weather stations. And since insurance is triggered at a certain point, it might be necessary to multiply the sensors, and to put at least one station at the entrance and at the end of the valley.