COP26 in Glasgow has passed. It is therefore time to add some information to the agricultural carbon dossier that I published at the beginning of summer 2021. In this dossier, I spoke at length about carbon storage in agricultural soils and I also introduced at some length notions about the carbon markets in place. This previous dossier has been updated with the information in this blog post.

While we may have smiled or choked on the speeches by Jeff Bezos – CEO of Amazon, Qatar and its green stadiums, Greta Thunberg’s tweets on carbon offsetting , or listening to the very nice speech by the Prime Minister of Barbados, it is necessary to go into a little more detail about what was actually agreed. We will not discuss COP26 in general here – some bloggers and newspapers have done this extensively (Carbon Brief, Bon Pote, Reporterre, Youmatter…), nor about its carbon footprint, which is obviously not very good at all, we will instead come back to the outcome of Article 6 of the Paris Agreements to make the link with the carbon markets that I mentioned in my previous report, and we will recall the main decisions of COP26 with regard to agriculture and forests.

I did not attend COP26. But in the interests of popularisation and knowledge sharing, I am contributing here to facilitate understanding of the carbon issue in agriculture – which is so complicated – and which many players are trying to grasp, rightly or wrongly. This blog post, much shorter than the previous ones, is the result of a lot of reading, mainly online,

Enjoy your reading!

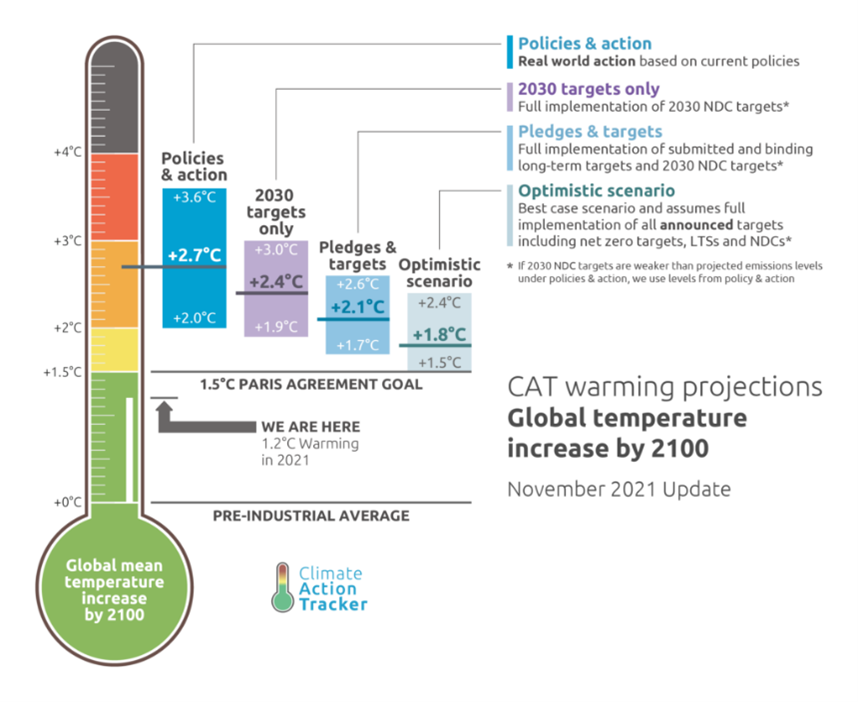

Figure 1 Climate Action Tracker (CAT) projections. Four scenarios are represented, taking into account or not the NDC commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions) that we will discuss below, net zero emission targets, or long-term strategies.

Soutenez Agriculture et numérique – Blog Aspexit sur TipeeeArticle 6 of the Paris Agreements

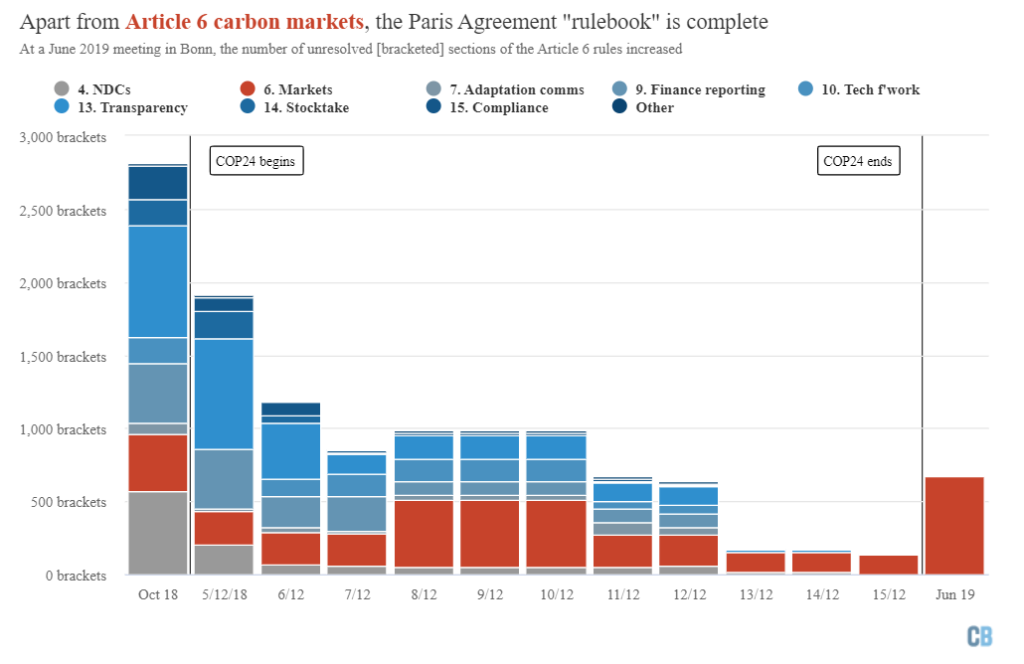

This was the ugly duckling of COP25, one of the only articles that had not yet found an acceptable outlet for all parties (Figure 2). Article 6, which mainly deals with the way emission reductions will be accounted for (the establishment of carbon markets and trading mechanisms), gave participating countries a hard time

Figure 2. The number of drafted sections that had not yet reached consensus by June 2019. In particular, those around article 6 are shown in red and it can be seen that this number is increasing again in June 2019 compared to previous dates

As a result of COP26, three mechanisms have been agreed upon, presented respectively in sections 6.2; 6.4 and 6.8 of Article 6 of the Paris Agreements.

Section 6.2

This first section of Article 6 refers to the establishment of a new market mechanism dedicated to the bilateral exchange of mitigation outcomes between countries; or in other words ITMOs (internationally transferred mitigation outcomes); the idea being that each country can collaborate in a general mitigation of their impact on the climate. These new ITMO supports are in fact supposed to replace the old credits that were defined in the framework of the Kyoto Protocol that I had introduced in my previous dossier (those from the Joint Implementation mechanism or JI, and the Clean Development Mechanism or CDM). Note that :

- This new market is a voluntary carbon market. It has nothing to do with the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – which is a bond market – that I introduced to you in my previous blog entry (in particular, I told you about the acronym ETS – Emissions Trading Scheme – and its European leaning EU-ETS, EU standing for Europe). Nevertheless, one can imagine links between this market and the existing ETS systems

- This new market is a market between countries, not between companies. With this new market, countries and governments are therefore able to enter the voluntary carbon market, something they could not do before, notably because there was no method deemed sufficient to avoid double counting of emissions (more on this later).

In my previous dossier, I also reminded you that, since the signing of the Paris agreements in 2015, each country had to commit to putting in place actions that would allow it to limit the evolution of temperature in 2100 compared to the pre-industrial era of 1850. Rather than actions, you will often find the term “Nationally Determined Contributions” or “NDCs”; we can talk about NDC actions or climate pledges. Note that some NDC actions are conditional – meaning that countries will make commitments on condition that… – while others are unconditional, meaning that these actions will be carried out without any preconditions (you will find the terms Conditional and Unconditional NDC). I would like to take this opportunity to remind you that the countries that signed the Paris Agreement were supposed to arrive at COP26 with updated NDCs, or at least with NDCs if they had not prepared any in the past (this was obviously not the case, but that’s another topic…).

In this bilateral market, the ITMOs can thus be used by the countries to comply with their NDC. The whole point of the debate on this new market was to define what could be exchanged with the ITMOs, because when you look at it more closely, it is a bit of a party. Some countries define their NDC over one year, others over 5 years, and still others over a longer term. Not all countries include the same sectors in their NDC. Nor do all countries agree on what an ITMO should be. I deliberately did not talk about ITMO credits because some countries would like ITMOs to be counted as emission reductions (counted as CO2 equivalent, for example), others would like it to be counted also in terms of renewable energy capacity or hectares of planted forests – in short, an ITMO could be anything you want. The second big issue was to avoid counting emissions results twice (basically granting ITMOs to both the buyer and the seller); it sounds a bit crazy when you put it like that but it’s the reality. We will discuss this in more detail in section 6.4 of article 6.

What we can learn from COP 26 about this section 6.2:

- A “Corresponding Adjustment” mechanism has been put in place to avoid double counting of ITMOs in this bilateral market, including a set of methods to try to harmonise the diversity of NDCs of each country (which means that we are not completely out of the woods). This adjustment mechanism will be discussed again in section 6.4 of Article 6.

- ITMOs could be emission reductions measured in tonnes of CO2 or kilowatt hours of renewable electricity

Section 6.4

This second section of Article 6 deals with the establishment of a second market mechanism, called the Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM). This mechanism – which I introduced very lightly in the previous dossier – is a sort of reworking of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) set up under the Kyoto Protocol. Note: There is only one SDM mechanism here, unlike the two mechanisms that existed in the Kyoto Protocol (CDM and JI). One of the explanations has to do with the fact that, following the Paris Agreements, all the signatory countries committed themselves to fighting climate change. There was therefore no longer any real reason to separate the trading of credits from industrialised countries to other industrialised countries (JI projects), and from industrialised countries to developing countries (CDM projects).

In the same way as in the previous bilateral market, the objective is to account for and trade ITMOs. But this time, local actors (companies, individuals, etc.) can also participate in the exchange, purchase or sale of ITMOs. These ITMOs can be used by a country to achieve its NDC commitments, but also by a company wishing to achieve a zero-carbon trajectory that it has set itself. The fact that the same ITMOs can be used by both the private sector and government raises questions. Some will say that this is a way of encouraging the development of carbon projects. Others will argue that it could discourage government action by relying on business. It remains to be seen whether ITMOs sought by both companies and governments should be used primarily for NDC commitments or not. We could perhaps see a market split in two, with carbon projects reserved for governments and a market that would be used by private companies. The debate remains open….

One of the big issues surrounding the SDM market was what to do with the credits generated under the former Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). With the Paris Agreements taking precedence over the Kyoto Protocol from 2020 onwards, a decision had to be taken on what to do with these old credits (known as CERs – Certified Emissions Reductions). Some people are even talking about ‘zombie’ credits in the sense that we could end up with a transfer of the old CER credits to the new ITMOs. This is all the more worrying given that, with the low price of carbon credits a few years ago, the accounting of CER credits was not necessarily very interesting back then but could be more interesting now. These credits could therefore flood the new private market and thus drive down the price of ITMOs simply by following the law of supply and demand. In general, this is a problem because these old CDM projects already exist, and will not contribute to further greenhouse gas emission reductions.

What can be learned from COP 26 on this section 6.4:

- Approximately 300 million old CER credits will be converted into ITMO credits and will thus be added to the ITMO credits generated in the future. Even if this figure seems huge, it remains a minority share of the total CER credits that could have been converted. Some observers will go so far as to say that these zombie credits are interesting in the sense that they will make it possible to quickly test the new SDM mechanism of the Paris agreements since they will be available very quickly. Others will say that the very low market price of CER credits reflects the low quality and environmental integrity of the projects linked to these credits, and that they will not find many buyers anyway.

- A “Corresponding Adjustment” mechanism has been put in place to avoid double counting of ITMOs. All ITMOs generated in the context of the SDM market, whether to meet a country’s NDC commitments or for any other international mitigation objective, must take into account the corresponding adjustment mechanisms. Note that “any other international mitigation objective” is relatively vague, and this is the problem with Article 6.4.

- A “Share of Proceeds” mechanism has been set up to provide a climate adaptation fund for developing countries. Under the SDM, 5% of the funds generated from the sale of ITMOs will go directly into the adaptation fund, not to the ITMO seller. This is a mandatory action within the SDM market, not a voluntary commitment. Note also that this 5% threshold does not apply to ITMOs generated in the bilateral market. In addition, it is added that 2% of the ITMOs traded will be directly removed (again, this is mandatory) in order to accelerate the fight against climate change (this objective is referred to as the OMGE target for “Overal Mitigation in Global Emissions”). Here again, this 2% ITMO removal will not be applied in the bilateral market but only in the private label market. In the private market, a seller who trades 100 ITMOs would actually sell only 93 (2 would be directly removed and the money generated with 5 of the ITMOs will go directly into the adaptation fund for developing countries).

- Disagreements over carbon projects or ITMO trades will be handled by an entity independent of the project or trade parties (this was not the case at present)

Section 6.8

This third section of Article 6 deals with the implementation of a final mechanism which is not a market mechanism. No trading system is set up. It could be activities similar to the other mechanisms described in sections 6.2 and 6.4 of the Paris Agreements – support for a new wind farm, for example – but without buying and selling the resulting CO2 savings. These could be seen as loan or development assistance schemes. A Glasgow Committee has been launched on this non-market mechanism to take forward the development of international cooperation on this issue.

Agriculture and Forestry

In the previous dossier we talked extensively about carbon storage in agricultural soils and forests. We will not go into detail on this. COP26 was nevertheless an opportunity to work on agricultural and forestry issues. We are only interested here in the link with carbon, even though many other issues around biodiversity, land and human rights could be widely discussed. A small victory, however, is the fact that the term “agro-ecology” was mentioned and discussed for the first time during COP26.

- Methane

More than 100 countries are reported to have committed to reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels (The Global Methane Pledge). This is quite a strong commitment, with the objectives of introducing rules to measure, report and verify methane emissions, rules to limit flaring and venting, and rules to detect and repair leaks. Although the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has also been mentioned as one of the ways to tackle methane emissions in the agricultural sector, some observers consider that the promises of methane reductions are much more focused on fossil fuels than on livestock farming and other sources of agricultural methane emissions.

- Deforestation

When we know the carbon content of forest soils and the capacity of forests to store carbon, we can only be satisfied to fight against any type of deforestation. More than 130 countries have reportedly signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, pledging to work collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. In addition, the UK and Indonesia are reported to have launched a declaration on Forest, Agriculture and Commodity Trade (FACT) to support sustainable trade between commodity producing and consuming countries. Both declarations include financial pledges for the restoration, protection and sustainable management of forests, and to support local and indigenous communities.

These declarations were soon met with criticism because the commitments were seen as being very close to those made in the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, which already aimed to halt deforestation by 2030 – a way for some to shift the timing of action against deforestation once again. The declarations could be interpreted as a commitment to sustainable forest management rather than a real end to deforestation.

A final point to add here: CER credits historically generated by avoided deforestation under the UN REDD+ programme can no longer be used (so they will not be converted into ITMOs) because these projects would not represent a real and additional reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

- Nature-based solutions

This includes nature-based solutions that are intended to support the fight against climate change, such as the conservation and restoration of ecosystems and land management practices. In the text of the Paris Agreements, direct references to nature-based solutions have been removed and replaced with “protect, conserve and restore nature and ecosystems”. There is also support for the fact that the terms “forests” and “terrestrial and marine ecosystems” have found their way into the text as sinks and reservoirs for achieving the climate goals that countries have set.

In early drafts of the Article 6 text, carbon ‘removals’ (broadly speaking, carbon storage) were limited to the agriculture, forestry and land use sector. In the final decision on the text, carbon ‘removals’ were expanded and the reference to the land sector was removed. This means that carbon removals could also be achieved through storage technologies

- A small numerical note

The Agriculture Innovation Mission for Climate (AIM4C) was launched by some 30 signatory countries, including the United States, the United Arab States, Australia, Brazil, and Ukraine. Several billion euros have been put on the table, in particular to finance innovations around “climate-smart agriculture”, whose very techno-solutionist orientation could be a cause for concern. I invite you to read my dossier on digital technology as seen by the human and social sciences:

Conclusions

COP26 was once again the occasion for great commitments and fine speeches. The real question is whether these commitments will be kept. The complexity of the 29 articles of the Paris agreements, and especially of article 6, lies in the vocabulary used. And when you see the hours spent discussing the use of this or that word or verb in order to reach a consensus, you realise how important terminology is here. Reading the articles is open to (much) interpretation, and this is where the problem lies: a gateway for all those who have no interest in combating anthropogenic climate change. The devil is in the detail and it is necessary to always distinguish in the texts what is voluntary and what is mandatory, what is conditional and what is not, or what time horizons are described. In short, if you have trouble sleeping, you have some reading to do, and beware of ambiguities…

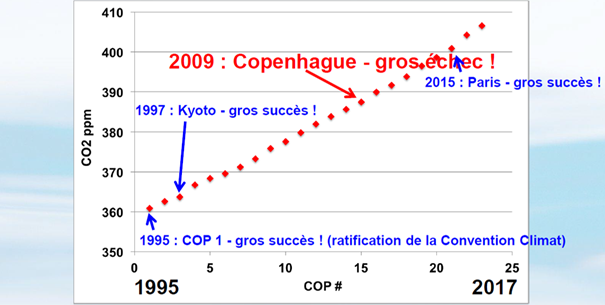

A little game for those interested: We could have fun (or not) extending Jean-Marc Jancovici’s graph (Figure 3) to follow the evolution of the atmospheric CO2 concentration following COP26. Not sure if we will come out of it with a smile…

To go a little bit further

Three very good articles from Carbon Brief:

- https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-q-and-a-how-article-6-carbon-markets-could-make-or-break-the-paris-agreement

- https://www.carbonbrief.org/cop26-key-outcomes-for-food-forests-land-use-and-nature-in-glasgow

- https://www.carbonbrief.org/cop26-key-outcomes-agreed-at-the-un-climate-talks-in-glasgow

Additional webography

- https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/energy-transition/111021-cop26-article-6-talks-grind-forward-as-countries-seek-common-ground

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/interactive/2021/glasgow-climate-pact-full-text-cop26/

- https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/article-6-cop26/

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6021

- https://ukcop26.org/cop26-keeps-1-5c-alive-and-finalises-paris-agreement/

1 thought on “The race for carbon in agriculture (2): a look back at COP26 in Glasgow”